Mexico City: A City of Extremes Drought to Deluge, Water Scarcity to Stormwater Abundance

By: Mairene Rojas-Tineo

From the summer of 2024 to the summer of 2025, Mexico City swung dramatically between two extremes. The city experienced the looming threat of an extremely dry rainy season in June of 2024, and, a year later, the heaviest rains seen in decades. Although this was previously considered a climate anomaly, the alternating rhythm of drought and deluge is becoming increasingly normal and the new hydrological identity of Mexico City and its surroundings. Due to this sinusoidal behavior, the city’s relationship with water has been evolving over countless centuries. But, now, a new challenge has arrived: managing an abundance of rain within a very short window of time.

A year prior to one of the rainiest Junes in Mexico City’s history, Mexico City was preparing for “day zero”, the date when the municipal water system could no longer provide large portions of water to the city’s residents. The reservoirs that provided Mexico City with almost 25 percent of its potable water reached exceptionally low levels after repeated insufficient rainfalls and over-extraction. Due to below-average precipitation and La Niña patterns, such as cooler than average sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, much of Mexico’s central region was facing extreme drought. More specifically, high pressure zones in the atmosphere 1) blocked clouds from developing and, 2) did not allow warm air to rise; two processes needed for the production of rain. To make matters worse, infrastructurally speaking, Mexico City’s poorly planned and exhaustive water systems caused the ground to sink at alarming rates; making it significantly harder for rainwater to seep into the drained aquifer.

However, in 2025, the inverse occurred. By June, the start of the rainy season in Mexico, the skies did not stop opening to release rain. Over the span of 25 days, more than 220 million cubic meters of rainwater fell over Mexico City. The city’s Ministry of Water and Sustainable Management reported that this was the largest volume recorded since 1968; an unprecedented event in recent history. The rain did not stop there. In July, a staggering 298 million cubic meters of rain fell. This figure is enough to fill Mexico City’s massive “Estadio Azteca”, which seats over 83,264 people, 196 times over. Considering the extent of the rainfall in June and July, the city faced a compounded struggle to adapt to the unexpected rainfall.

This shift in meteorological activities is driven by the complicated transition from La Niña to El Niño patterns over the Pacific Ocean. Previously, La Niña suppressed storm activity in the region. But, El Niño flipped the script and brought amplified rainfalls over central and southern Mexico. This transition, in turn, exacerbated atmospheric evaporation, increasing the amount of water vapor in the air and condensing to cause intense rainfalls.

To further intensify the rains caused by El Niño, the 2025 rainy season was characterized by an uptick in local tropical cyclones and wave activity in the Pacific and Atlantic basins. Although these storms did not hit Mexico City directly, they moved huge amounts of moisture to central regions of Mexico, triggering long-lasting storm clouds and potent rains over Mexico City. The already-increased atmospheric instability worsened as warm, moist air from the ocean mixed with cooler air in the upper atmosphere. Fast winds, tropical moisture, warm sea temperatures, and high altitude levels in Mexico City combined to create the perfect, but destructive, setup for a strong storm.

While the intense rains did some much needed replenishment of water sources, it also revealed Mexico City’s deep vulnerability to rainfall, and improper infrastructure to withstand it. Without adequate urban planning, rain can become a hazard, rather than a natural resource. All over the capital, streets became rivers, train stations flooded, and parks resembled lakes. Entire quadrants of neighborhoods were covered in a mix of stormwater and sewage. However, the problem is not inherently rain. It is equally a result of a city that has been designed to shed water, rather than absorb it back into the aquifer. The hydrology of Mexico City has increasingly become misaligned with its pre-colonial and post-colonial infrastructure. As the city continues to flood, this becomes more apparent each year.

To understand how the city reached this point, it is essential to understand the geographic and historical foundation of the region. For a brief summary, the area that is now called Mexico City, but was previously the Mexica capital, Tenochtitlan, was built upon several lakes and thrived on an intricate network of natural and artificial canals, floating gardens (chinampas), and wetlands prior to colonization. Water was considered an integral and necessary part of daily life, rather than an enemy. Although floods were still prominent centuries ago, they were accommodated by buffer designs meant to alleviate the impact of heavy rains, unlike in present day Mexico City. However, everything changed when the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century. In pursuit of permanence, Spanish settlers began a centuries-long effort to drain lakes, fill wetlands, and change the natural landscape of the city. Rivers were rerouted, covered, and channelled to expel water from what had once been a basin of water abundance.

This Spanish-imposed rejection of water continues to haunt the city. Paved streets with impermeable infrastructure now cover most of urban and peri-urban Mexico City, drastically decreasing the capacity with which soils and aquifers can absorb rainfall. Since groundwater extraction far outpaced the natural recharge of aquifers, the city also began to sink several centimeters each year. Therefore, yes, flooding is certainly directly correlated with intense rains, but it is also caused by the rain having no designated place to go. Modern Mexico City floods because it was designed to displace water, not to manage and coexist with it.

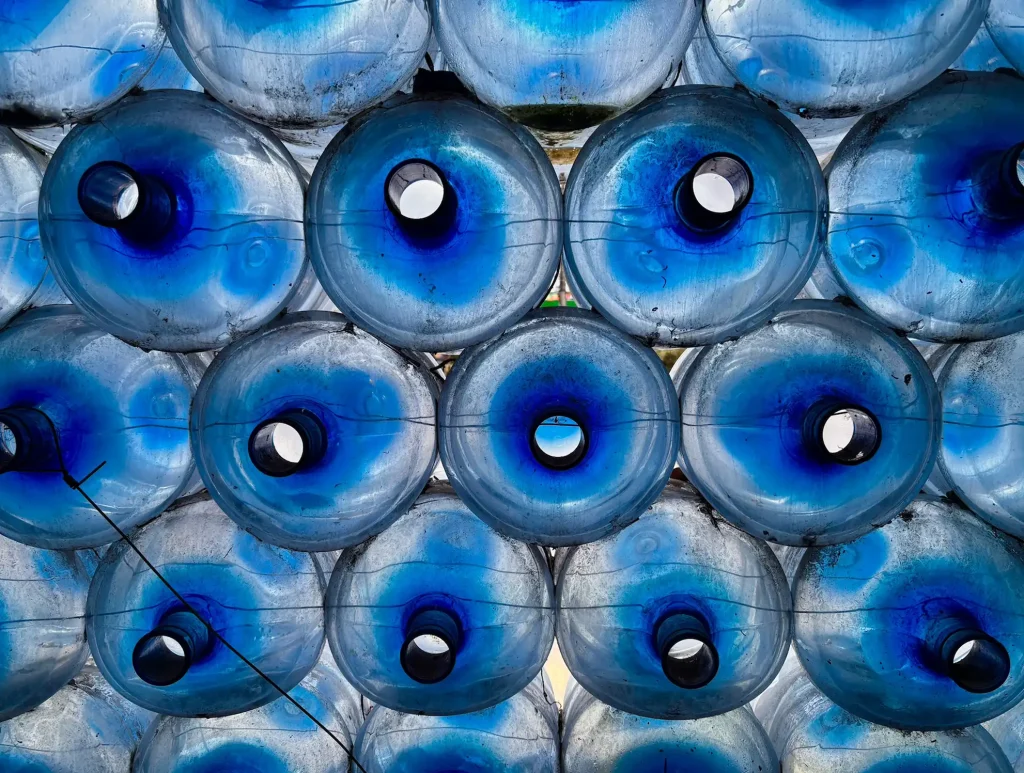

In response to these historical and systemic failures, organizations like Isla Urbana have emerged as pioneers of a new approach to water management in urban and peri-urban environments. Isla Urbana treats rain as an asset to be harnessed rather than a problem to be disposed of. Since 2009, Isla Urbana has worked to install rainwater harvesting systems throughout Mexico, particularly in underserved communities where municipal water supply is inconsistent and unreliable. Rainfall is captured from rooftops, passed through a series of filters to remove contaminants, stored in covered cisterns, and made available for human contact. Through this work, many Isla Urbana workers, including myself, have learned to appreciate rainfall as a source of hope and water access, rather than something to be feared and hated. Step by step, Isla Urbana is gradually guiding Mexico City toward a renewed respect for water; one that echoes the values held in pre-colonial times.

What makes rainwater harvesting particularly effective is that it addresses multiple dimensions of the water crisis. 1) It reduces dependence on overly-used centralized supply networks. 2) It captures and stores rainwater that would otherwise contribute to flooding dangers. 3) It helps recharge local groundwater systems by slowing rainwater runoff and allowing more of it to percolate into underground aquifers. 4) It provides clean, reliable water to families, with many public health benefits. In other words, rainwater harvesting systems have the potential to restore hydrological balance in an environmentally unjust city that has lost its capacity to naturally absorb rainwater.

More globally, rainwater harvesting aligns with broader goals of climate adaptation and resilient urban planning. As weather patterns, such as the El Niño and La Niña phenomena, cities must learn to manage water in a way that prioritizes supply, timing, storage, and flow rate. Similar to the buffers created prior to Spanish conquest in Mexico, harvesting rainwater provides on-site buffers that alleviate the negative impacts of rainy seasons. During the rainy season, rainwater can be collected to mitigate flooding, and, during dry periods, stored water can be used to reduce demand on centralized water systems. Hence, it is crucial to integrate these systems into public buildings, parks, and industrial hubs!

The potential is enormous. Mexico City receives more rainfall annually than London, a city known for its ubiquitous rainfall. So, the problem in Mexico City, as established previously, is not the lack of rain; it is the inability to properly use it. It is crucial for our society to rethink how we manage urban water cycles in a way that celebrates rain, rather than disregards it. Parks should be designed to double as water basins. Newly created streets should be permeable, rather than sealed. Green infrastructure, such as wetlands and rain gardens, should be considered necessary functional components to a city’s system. Rainwater harvesting should become more and more common in urban infrastructure.

Rain in Mexico City is no longer an occasional event. It has become a norm during the summer months. It is an increasingly intense phenomenon that requires a novel system built on flexibility, absorption, and just redistribution of water resources. Therefore, the water crises of 2024 and 2025 are not necessarily extremes; they are parallel images of a deeper structural failure and vulnerability. Both events arose from a disconnect between Mexico City’s built environment and its natural hydrological tendencies. Through all of this, rainwater harvesting offers a trajectory towards a newfound urban water resilience. But, it must be accompanied by innovation, imagination, and investment.

A new sustainable water system requires the understanding from centuries of ecological wisdom all over Mexico. By learning from the past and planning for an uncertain future, Mexico City can become a global model for how to thrive in extreme temperatures and climates. Our globe’s goal should be to live with rain sustainably, ethically, and equitably.